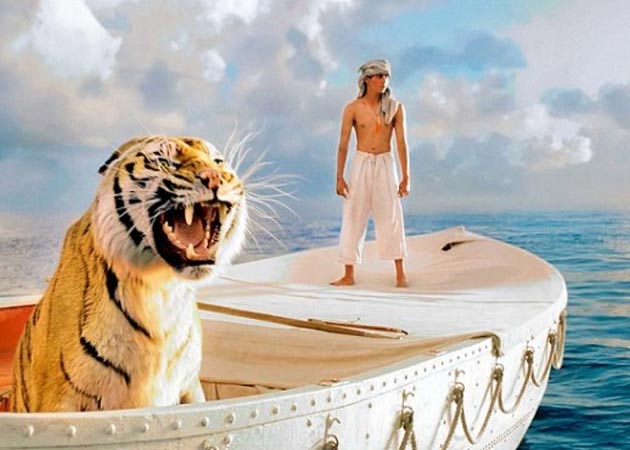

‘Life of Pi’: a bit too ‘pie in the sky’

Here I discuss how both the film and the book offer a great opportunity for reflection on important religious questions, but that its false dichotomy of disenchantment/re-enchantment, rational science/irrational religion, offer a rather superficial view of religious belief.

http://www.lifeofpimovie.com

Life of Pi had been recommended to me by friends and students for many years: ‘You’d love it.’ Now the film is out and people have recommend it as well: ‘See it. You’d love it.’ People seem to really like this story—or Story, as the author suggests. So, I’ll tread lightly in saying: ‘I read it. I saw it. I’m glad I did… but… [sigh].’

However, whether I didn’t love it or like it, per se, does not really matter at all. Yann Martel won the Man Booker prize (2002), and I should say deservedly so, though I have probably enjoyed other winners’ books a bit more. (The Sense of an Ending, by Julian Barnes (2011), is a beautiful read.) On the whole, the book is very cleverly constructed, well-researched, and the writing style is effective. Most importantly, though, it presents an opportunity to reflect on some religious and philosophical insights. It is indeed refreshing to see the success of a book and a film with traditional religions (Hinduism, Christianity, and Islam) at the forefront of its plot. Indeed the claim made is that this Story will make one believe in God. With a dearth of substantial cultural objects dealing with questions of religious belief and of what is most ultimate in life, Life of Pie presents much more substantial material for reflection than is typically encountered in popular culture. However,the religious perspectives are not as profound as they may seem to many readers/viewers, and the reason why these perspectives might seem to some as more profound than they are is precisely the lack of substantial exposure to and discussion of the truth of religious traditions.

One of the main themes of the book—perhaps the main theme—can be characterised by the discussion, around the late 1990s and turn of the millennium, of ‘re-enchantment.’ This period witnessed a kind of return to the mystical and the importance of ‘story’ in popular culture, as opposed to hard facts. This kind of a discussion had been going on for some time in philosophy and critical theory, especially since the work of Max Weber, who in elaborating the process of ‘rationalisation’ in Western society, used the term ‘disenchantment’ to describe what was happening. This is close to a similar word, often thought to have influenced Weber, spoken of by Schiller: Entgötterung, or de-divinisation. Rationalisation, in simple terms, can be seen as issuing from the Enlightenment ideal of liberation from irrationality, e.g. superstition, religion, tradition, authority. Tapping the power of human rationality, increasingly liberated from the restraints of irrationality, would bring about a quasi-messianic deliverance of society from its problems. However, as the power of human rationality, left to its own devices, increasingly is acknowledged as a force both for great good (such as scientific advancements, democracy, etc.), as well as great evil (genocide, the two world wars, totalitarianism), a kind of crisis of reason emerges in society. Thus, the antithesis of disenchantment—enchantment—makes itself heard again in what is referred to sometimes as ‘re-enchantment.’ The emergence of re-enchantment indicates that human beings are not nearly as rationalistic as the Enlightenment ideal of a completely rational society portrays and that we actually long for mystery and something more than the sheer facticity of life as rational processes. And in some cases a strong programme of re-mythologisation emerges to counteract the drive toward mechanistic rationality. Popular culture in the late 1990s and turn of the millennium saw a marked increase in interest in cultural objects with the earmarks of re-enchantment. For instance, one can look to the cult success of The X-Files, emphasising the paranormal’s defiance of empirical rationality. Further, in 2001 two major film phenomena emerged, with the first The Lord of the Rings film, and the first Harry Potter film, after the book’s launch in 1997. One cannot underestimate the fervour surrounding these events. This has continued in the recent vampire craze, as well as the number of exorcism films (not to mention the number of people requesting the services of exorcists). Thus we should ask ourselves: why? Why are people so drawn to these stories of fantasy? I will not address this here, but it is certainly worth thinking about.

Another book/film combination that closely resembles Life of Pi, is Daniel Wallace’s novel, Big Fish (1998), which was became a film in 2003. In Big Fish we see the same theme at play: which story is better? The one that is told factually, or the one that is made fantastic? The story depicts the transformation of Bill Bloom, a fact-seeking journalist, who in contempt for his fabling father goes in search of the facts of his father’s life. Bill finds that some of the fantastic stories his father told were based on real events, or facts, but that he was prone to exaggeration and outright fabrication. Bill becomes sympathetic to the difficulty of his father’s life and begins to understand why he chose to alter these realities in a fabulous way. By the end Bill chooses to embrace the more fantastic story about his father, rather than the cold facts, and it is in doing so that his own life, for the first time, takes on joy and meaning. This is essentially what Life of Pi is suggesting as well.

In the penultimate chapter of Life of Pi, Pi recounts his story to two Japanese officials who are investigating the sinking of the Tsimtsum. Interestingly, tsimtsum is a term from Jewish mysticism, meaning something like ‘withdrawal’, which here can signify Pi’s withdrawal from the known world into an unknown world, as well as his interior journey into the unknown. Pi confronts them with with two stories. One that is fantastic, with animals, and a strange island, which the officials do not believe at all; then one which is far more believable, which is the one that probably actually happened. In this latter story it becomes apparent that Pi’s tale is a kind of allegory, and that he was not stranded with animals, but with his mother (Orange Juice, the orang-utan), a crew member (the zebra), and the French cook (the hyena). Pi himself is Richard Parker, the tiger. He saw the French cook kill and eat the crew member, then murder his mother, and then Pi, in turn, killed the French cook, and even ate some of his flesh, partially to survive and partially as revenge. At this point the reader is implicitly asked to choose which story is the better one:

[Pi:] “You can’t prove which story is true and which is not. You must take my word for it.”

[Mr. Okamoto:] “I guess so.”

[Pi:] “In both stories the ship sinks, my entire family dies, and I suffer.”

[Mr. Okamoto:] “Yes, that is true.”

[Pi:] “So tell me, since it makes no factual difference to you and you can’t prove the question either way, which story do you prefer? Which is the better story, the story with the animals or the story without the animals?”

Mr. Okamoto: “That’s an interesting question.”

Mr. Chiba: “The story with the animals.”

Mr. Okamoto: “Yes. the story with animals is the better story.”

Pi Patel: “Thank you. And so it goes with God.”

This last line, of course is meant to be fecund. (By the way, Okamoto, in Japanese has connotations of one who is methodical, logical and prefers order. Chiba is a hebrew word indicating love. The more likeable and pleasantly naive of the two is Mr. Chiba.) It could mean that God prefers the animal story, and thus looks compassionately on Pi’s ordeal and understand that Pi tells this story in order to mediate the horror of these events. It could also mean that we should believe that there is a God because it makes for a better story if we do so.

There are two problems I have with this. The first involves the simple dichotomy between the enchanted story and the disenchanted story. We are faced with a kind of either/or. However, both positions are inadequate. On the one hand, there is sympathy for Pi’s effort to make meaning of a largely absurd happening, perhaps so as to preserve himself while stranded, and not face devastating guilt and grief for all that he encountered. In many ways, what he faced would simply be too much to bear for anyone, let alone an orphaned boy. Since, in the more fantastic story, Pi is both himself and Richard Parker, the tiger, we can see that he is trying to make sense of an internal struggle. He is still himself, but the situation also brings out an animalistic need for survival. It is interesting to note that Martel chose the unusual name, Richard Parker, based on a character in Edgar Alan Poe’s only novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, in which three men are stranded on a boat, and the character Richard Parker is eaten in order to sustain the other two. Many years after this novel, three Australian sailors were stranded at sea and ate a cabin boy, also named Richard Parker, and this became the first case where cannibalism was charged as a crime upon the high seas. This indicates the importance of the fact that Pi has to cope with having resorted to cannibalism himself, though in a most dire situation. The film largely left this component of cannibalism out.

Nonetheless, there is something harmful in simply adopting a coping mechanism as true and using this as an interface with those we are afraid might not understand our trials. Though there must be mediation of one’s traumas in a way that cannot be accomplished simply in cold, objective ways, flight into fantasy is clearly harmful as well. Though the more fantastic story is the better story in many ways, there is still something duplicitous about it. Not only are there ethical and psychological problems with this, but also in the way in which it intends to say that religious stories operate in the same manner. One could go on at length on this idea, but there is a danger in seeing the Christian gospel narratives as coping mechanisms developed in order to make sense of a tragic circumstance. Though, many in the contemporary world do indeed see these narratives in this way. There is much more at stake in Christianity than this, and other religions would likely agree in their own right. Myth plays an important role in religious traditions, but religions like Christianity cannot simply be seen as mythological. This would be a grave misunderstanding of the origins of Christianity and how it emerged as a world religion. So it is dangerous to equate the two or even to make too many connections, which would be rather tenuous at best.

The second issue I find problematic is the implication that: whether there is a God or not, it makes for a nicer story when we believe there is a God. Something of a Pascalian wager is being put forth here: that whether there is a God or not, one will have a better life if one believes in God, and so it is worth believing even if there turns out to be no God. And I think that in many ways there is wisdom to this adage. Not so much for the ‘wager’ aspect of it, but because the best way to come to know and love God is by loving one another. In my own life, the more I have tried to love those around me and to minister to people, the more I have known God’s love, and have experienced it as the most true love I have ever known. One can make abstractions about God’s love, doubting it as a possibility, perhaps waiting for more substantial proof. But I defy anyone to commit oneself to enhancing the lives of others, with all one’s mind and heart, and not to have a profound experience of God’s love. In this vein, Martel has a fascinating quote, that I think is particularly relevant in our times where we prefer to remain undecided about religious truths: “It was my first clue that atheists are my brothers and sisters of a different faith, and every word they speak speaks of faith. Like me, they go as far as the legs of reason will carry them—and then they leap. I’ll be honest about it. It is not atheists who get stuck in my craw, but agnostics. Doubt is useful for a while. We must all pass through the garden of Gethsemane. If Christ played with doubt, so must we. […] But we must move on. To choose doubt as a philosophy of life is akin to choosing immobility as a means of transportation.” Indeed there is a grave danger of being paralysed by doubt. Just as there is a danger in the false certainty that rationalism often claims, as well as in the false certainty of fundamentalism—both are two sides of the same coin—there is danger in a fear of commitment that plagues doubt, and that remaining undecided can often be as harmful as making the wrong choice.

But does this mean that religions do not or should not claim that they are true, but simply good stories that are better than the materialist story? I would doubt that the martyrs of Christianity, for instance, died for the sake of a story without caring whether it was true or not. As finite humans, we may not have a clear cut way of knowing which stories are true and which are not, but it clearly matters whether they are or are not. It would be shamefully scandalous if people devoted their entire lives to a religion that was really just a story loosely based on real happenings, but wildly and fantastically fabricated in order to make oneself feel better about a tragic situation. Though, again, this is precisely what many modern sceptics think Christianity did do. For this perspective there is no scholarly justification. It is important to note that the conviction required for strong belief is not irrational, but actually demands a strong component of reason, as a graced ability to perceive beyond that which we can fully understand. There is something more like trust in this than a leap—opening oneself up to the embrace of One who is strangely familiar, rather than flinging oneself into an absurd void. This actually requires a robust sense of reason.

Closely related to the dichotomy between disenchantment and re-enchantment is that between rationality and irrationality, and this is central to Life of Pi, played out in the option for scientific materialism, or belief in God. He proposes that one is rational, the other irrational, but he clearly favours the irrational belief over cold, stark materialism. We see this in the protagonist’s self-given nickname, Pi; obviously a reference to the famous ‘irrational’ number, π: 3.14159…. The author comments in an interview: ‘It stuck me that a number used to come to a rational, scientific understanding of things should be called “irrational.” I thought religion is like that, too: It’s something “irrational” that helps make sense of things.’

The mistake of seeing religion or belief in God as irrational is reflective of a meagre understanding of reason. This implies that there is no relationship, or at least a significant gap between faith and reason. Some might agree that there is indeed a significant gap between faith and reason. But I would argue that this is due to a significantly truncated view of reason. It is indeed intriguing that mathematicians would dub a number that exceeds definability ‘irrational.’ This implies that reason is the process of determining things as clear and distinct, definite, without ambiguity. Traditionally, one might say that this sense of reason sounds more like the idea of ‘ratiocination,’ which is a faculty of reason, but not the whole name of the game. In some ways, rendering something completely determinate turns it into a mere object. The object becomes confined to the prison walls of the mind’s concept. But can all things simply be placed in such a box? If scientific rationality is only concerned with things which can be objectified without remainder, so that all loose ends are scientifically tied up, then what value do we place in things that cannot be so neatly packaged? Is art simply irrational because it cannot be completely, objectively defined, or because its meaning cannot be rendered completely determinate? Does that make the meaning indeterminate? Philosopher, William Desmond, would suggest rather the term ‘overdeterminate.’ Something determinate can be said, and an objective component discussed, but the meaning or the qualities of something overdeterminate exceed total definition. Instead of seeing that which exceeds total determination as a messy, unscientific remainder, perhaps this is expressive of a robust dynamism in our world. If the clarity and distinctness of an object’s qualities continues to elude us, is that not a cause for wonder, or astonishment, rather than frustration?

From a philosophical perspective, critical of a truncated notion of reason, as the ability to render something completely determinate, I find the use of the term ‘irrational’ unfortunate. Religion is only outside the realm of reason when the concept of reason is pared down in such a way that it refuses to acknowledge and appreciate that which eludes intellectual captivity because of its wondrous excess.

Religious traditions in their quest for God or what is most ultimate are not irrational. They are certainly not merely rational, though, either. When rationality is identified only with ‘ratiocination’ or that which empirically, logically, or mathematically determinate, then in a strange way, so-called ‘reason’ (but really rationality) becomes an irrational religion, because it begins to operate under the assumption that nothing outside of empirical observation can be known, and this is not a claim which can be rationally justified. The rationalist or scientist who concludes that there is no God cannot do so without violating the very rules of their rational or scientific system. Thus, it operates on the faith that the empirically observable is all that is important, and everything else is just woolly nonsense and childish wishful thinking. Scientific materialists become as naively believing in this kind of rationality as most ultimate, as any religious fundamentalist. Reason that does not see itself as pointing toward the transcendent with a religious comportment, ceases to be reason and becomes mere rationality, or ratiocination.

Martel presupposes the retracted notion of reason as ratiocination, and then stands opposed to it, favouring the irrational. Thus faith and reason are incompatible, requiring an either/or decision. We can see this in how he sets up a dichotomy between rational science and irrational faith in the two characters named Mr. Kumar. One is a science teacher who does not believe in God. His position is a common one today: “There are no grounds for going beyond a scientific explanation of reality and no sound reason for believing anything but our sense experience. A clear intellect, close attention to detail and a little scientific knowledge will expose religion as superstitious bosh. God does not exist.” The other is a simple baker, who is not formally educated but is a devout Muslim with a fundamental trust in Allah. He uses this very common Indian name to indicate their archetypal role, and that the dichotomy they represent is the essential theme of the novel. “The two Mister Kumars—one the science teacher, the other the mystic baker—and the zebra. One archetypal man—Kumar is a very common name in India, one reality—a Grant’s zebra, two understandings of that reality—one transcendental (“Allahu akbar,” God is great), the other materialist (Equus burchelle boehmi, the scientific name for a Grant’s zebra). The whole novel in one scene. How reality is an interpretation, a choice of readings, a choice of stories.” It is clear that Martel favours the believer over the materialist, and his novel uses the story of Pi to convince the reader as to why this is a better outlook. Yet, again, this juxtaposition is far too easy, and not adequate to the way in which faith and reason can and do interact splendidly.

There are many other points worth discussing—as I said, Life of Pi offers a significant opportunity for discussion—but as I have gone on far too long, I leave it to you to think about these things for yourself. In the end, I would recommend this film. I would even recommend to those who have not read the book, that you could see the movie and not really miss out on anything overly important. In some ways I would even say that the film is better than the book. I found it visually stunning and better able to handle some of the action sequences and the fantastic quality of what Martel was trying to communicate. The film also eliminates some of the scenes in the book which came across to me as rather forced. Similarly, it even provided better segues to many of the happenings in the plot, which in the book seemed not to flow very well. At first I thought of the addition of the romance between Pi and Anandi as typical Hollywood antics, but in the end I saw it as well-executed and a beautiful addition. On the whole, I think the reason this book and film appeal to so many is because it issues a rather superficial understanding of religion(s), which appeals to the rather superficial views of religion people tend to prefer in contemporary culture. I could harp on this idea further, especially the sense in which the book portrays religions as at once unitarian and as a kind of smorgasbord, but I’ll spare you that, at least.