An Imagination Worthy of the Eucharist

For the Seventeenth Sunday in Ordinary Time.

There is actually a surprising difficulty in discerning how to speak of this very well-known ‘miracle of the loaves and the fishes’. That difficulty does not present in the confusion over why they are referred to as ‘fishes’ instead of ‘fish’, which used to occupy my mind for most of the time the priest was giving his homily when I was a kid. The translation does read ‘fish’, and the story is actually labelled ‘Jesus Feeds the Five Thousand’ in most editions these days. Rather, the difficulty lies in how radically subversive this message is; subversive enough to make most people uncomfortable, when we really dig deeply into what is happening here. The real message herein has the power to shatter the kinds of idols people often form in the mind, and presents, then, the challenge of expanding the confines of our imaginations, which can have an all too easy tendency to shrink dramatically while we aren’t looking.

There is so much that could be said along these lines, but I want to stay with two simple, but very challenging ideas; rather than getting into a lesson in history and theology, fascinating as that might be. (Let me know… we can always talk about that later.) But I think these two points can give us more than enough to think about. And I think each of these two ideas touch upon the points in these readings that are meant to shatter our usual ways of thinking, and expand our imaginations to breadths, depths, and heights that are more attuned to how God wants us and needs us to see.

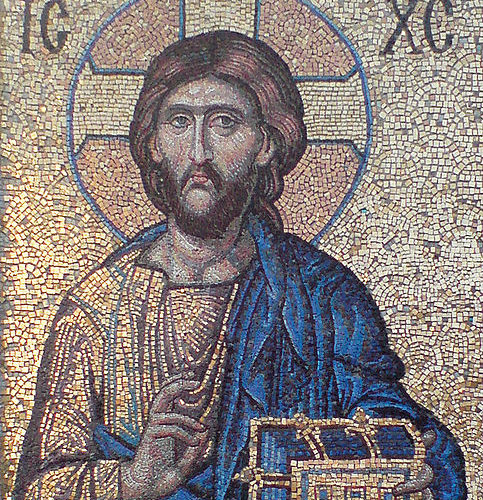

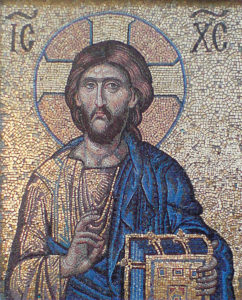

The first idea is: the Eucharistic rite in the liturgy is actually something far more subversive than we are often likely to think. Jesus’s feeding of the people is one of the main foundations of the institution of the Eucharist, obviously. The multiplication of bread places Jesus in the line of the great prophets like Moses and Elisha, but also as surpassing them. There is great symbolism in the disciples being told to collect the leftovers, being able to fill twelve wicker baskets. Jesus has fed the 5,000 men, but actually many more, because that number did not include the women and children present; the completion number 5,000 and its excess indicate that Jesus is able to extend his table to everyone who wants to abide, with such great abundance that there is a large quantity leftover. The gathering of twelve full wicker baskets symbolises the gathering and unification of the twelve tribes of Israel. This is seen as such a subversive act, that the people want to make Jesus their king, so that he can be used to overthrow the oppressors and re-establish the greatness of the kingdom of Israel. Jesus wants no parts of this human-all-too-human plan, so he goes and hides. Not because he is afraid, but because his vision of the Reign of God is far more radical, and much less subject to the limitations and selfish longings of their Procrustean imagination. His vision is attuned to the expansive way in which God sees; not the idolatrous, limited way humans tend to see. Jesus, thus, subverts the subversives. The vision for the future he repeatedly rejects, is as important and instructive as the vision he proclaims.

When we celebrate the Eucharist we become the Body of Christ, which is the Church, in most profound anticipation of the Reign of God. Every aspect of this shatters all borders, all divisions, all senses of selfish or covetous notions of property, all of the limitations placed on us by those who seek power and who oppress in greed. The Eucharist, not despite, but insofar as it is performed in particular locations all over the world, at different times, is still performed in simultaneous unity, all as one, at the same time, and thus transcends all time and space. Those we commune with are all of the people of God, past and future, including the angels and the saints; the space in which we commune is where heaven and earth come together to participate in a new heaven and a new earth; the time in which we commune is the fullness of time, and thus providing us with a glimpse of that vision.

The Eucharist helps shatter our limited imaginations, while also helping us dramatically expand in all senses the possibilities of imagination. It is very easy for us to shrink our imaginations to fit what we are told is possible by those in positions of power or authority. One of the most troubling aspects of our society today is the lack of real imagination. One might object and point to technological innovation, however this is not so much the imagining of something really new, but modifications on present technology–innovation. Even still, technology is only one aspect of our lives, despite the messianic hopes too often misplaced on it. Yet the utmost horizon of what most can imagine for the future is: more of the same, but perhaps a bit better, with better technology. This is the reign of the nation-state, not the Reign of God; the imagination of consumer capitalism, not the Christian imagination.

When we see a problem we know is an injustice that really must change we often feel helpless to do anything that will actually make a difference. It is difficult to imagine how things could be made different. How often is this the, perhaps tacit, message of our governments and systems, that say it is too difficult to change something; or that something is a good idea, but can’t be done; or that ‘we have no choice’, ‘it is unavoidable’, a ‘necessary evil’. How often does this give us the impression that some people don’t want things to change. As Christians, as the Body of Christ, we have a responsibility not to allow the logic of the powerful shrink our sense of imaginative possibilities. God provides us with a vision of how things should and can be. People today, in some cases, tend to have very little respect for real imagination, (that is, not consumer innovation), underappreciating what is required to nurture it, and/or canning any ideas that don’t fit the current way of thinking. We would do well, quite seriously, to wonder why that is.

The second idea is: faith is required in order to maintain and live out the imagination characteristic of members of the Body of Christ. When we become the Body of Christ in the Eucharist, this is not supposed to stop once we have been sent forth with God’s blessing; yet, many times it seems as though what is asked of us in the scripture readings just does not translate well to the ‘real’ world. So we blink a few times as our eyes adjust to the sunlight as we head for the parking lot, and return to the usual, typical way we are taught to think by society. This is problematic. Augustine, of course, is most famous for speaking of the two cities: the civitas terrena and the civitas dei, which can very easily be misunderstood. This does not mean that we have to separate ourselves from society and long for the end of our mortal lives so we can see heaven. It basically means that we have to try to see with the eyes of the Reign of God, and try our best to act as a member or citizen of the Reign of God, while living in tension with all of the messiness of our current social situation and how it thinks and operates. This means we have to have the faith to see things both ways, but most importantly, not abandon the imagination we nourish and maintain as members of the Body of Christ.

Look, for instance, at Jesus’s exchange with Philip, which we are told is a test. He picks on Philip because they happen to be in a place closest to Philip’s house, which is in Bethsaida, and so he would probably have knowledge of the bread situation in the area. When asked where they can buy enough food to eat, Philip immediately thinks in conventional terms. He has seen Jesus turn massive quantities of water into way more of the best wine than they could have ever drank, amongst other signs, and yet…. This is a good example of how we hear of a story like this, and then go back to our normal ways of thinking about economics, money, consumption, etc. Philip’s calculated reply, ‘Two hundred days’ wages worth of food would not be enough for each to have even a little’ is absolutely correct and rational. Besides, there’s no way the town probably even has that much food available to purchase at that moment, and how would we manage to prepare it–such might our own calculating minds deduce. So when we feel the compunction that people shouldn’t go hungry, that there must be a way… we can very comfortably remind ourselves that, despite what Jesus says, there’s nothing that will work to fix that problem, realistically, and many economists and politicians will be relieved and affirmed. This is also why we might wonder why the poor shepherd boy didn’t say, ‘no way can you have this, I need this, and it is not enough anyway’.

This is also why many theologians and exegetes try to adapt this story to our economically, scientifically discerning ears, explaining that: perhaps in seeing the boy share his food, they all decided to share food with one another, and there was more than enough to go around. That’s not a bad idea, but that is not what happened here. How badly we want to translate things of our faith into rationally acceptable terms that will be deemed acceptable to anyone. In other words, denying the mindset of the civitas dei so as to live more comfortably in the civitas terrena.

So how does one live in this tension of seeing with two imaginations, so as to ‘be realistic’, but at the same time not give in to that limited logic that is more marked by what is sinful about human beings than what is good? How does one maintain the kind of faith and imagination being described here? How, for instance, can we faithfully proclaim with the psalmist that, indeed, ‘the hand of the Lord feeds us; he answers all our needs’? The letter to the Ephesians provides some council. If we are indeed to take up the invitation to be citizens of the Reign of God, and truly live out our calling responsibly, there are some virtues that can be received as gifts of the Holy Spirit, if we are willing to accept them and gain proficiency in them. They are as follows. Humility (ταπεινοφροσύνης, tapeinophrosynes), which means being open enough to allow ourselves to accept being transformed in the ways of Christ; which might mean becoming a very different person than we are now, thinking in ways we are not used to, or that might not be very popular. Gentleness (πραΰτητος, prautetos), which is not the conventional sense, falsely implying weakness, but a gentle strength that comes only through faith, and so is an empowerment that knows just the right way of handling things, not too hard, not too soft. Along similar lines, but with important differences, Patience (μακροθυμίας, makrothymias), which can come by being sensitive to the workings of the Spirit, discerning the proper time for certain things, but with endurance, not merely being passive; ready to take action, and yet not being impetuous. And finally, Bearing with in Love (ἀνεχόμενοι, anechomenoi; ἀγάπῃ, agape), or seeing something through to its end in a way that is reflective of divine love. These may be fairly common words we might hear, but they are well worth reflecting upon in a deeper, more prayerful sense, that is attuned to our gifts and what God intends for them. If we are true to nurturing these virtues as a way of helping us be faithful citizens of the Reign of God, they can help us have faith in and maintain the kind of imagination characteristic of those who pledge to participate in the Eucharistic Body.

We are all citizens of some nation-state, but we are first and foremost citizens of the Reign of God. It is good to know and understand the conventional ways of thinking in our society, but it is a massive failure to allow those ways to imprison the imaginative possibilities given by faith in the Church. Perhaps we cannot alone bring about the kinds of changes we know must happen for there to be peace and justice, but as the Body of Christ, as Church, we can achieve more than any group socially contracted to nations, rulers, authorities, and powers over this groaning world. Then we might be able to leave open and pursue the imaginative possibilities of that which we glimpse in being attuned to the vision of the Reign of God, and having our imaginations expanded by the glimpse bestowed on us of that Reign. This is not some easy or conventional way. Easier ways of thinking will not only not be discouraged, but will be rewarded in the current society, humming along on everything that would make such virtues grotesque and hapless means with no true ends.

St. Paul the Apostle delivers an ‘exhortation’, to walk strongly in a manner worthy of the call that we have received, and so too has Pope Francis given an ‘apostolic exhortation’: Gaudete et Exultate, as well as several other beautiful writings on how we can bring our Christian vision to a world in need. It is easy for us to read these words, and be filled with hope, but then reduce this magnificent Christian vision to ‘Beach Boys philosophy’: ‘wouldn’t it be nice…’. Let us encourage one another, in the binding power and wisdom of the Holy Spirit, to maintain the imagination offered to us in faith, so that we might offer a true light to the world, and strive to bring this vision to light.